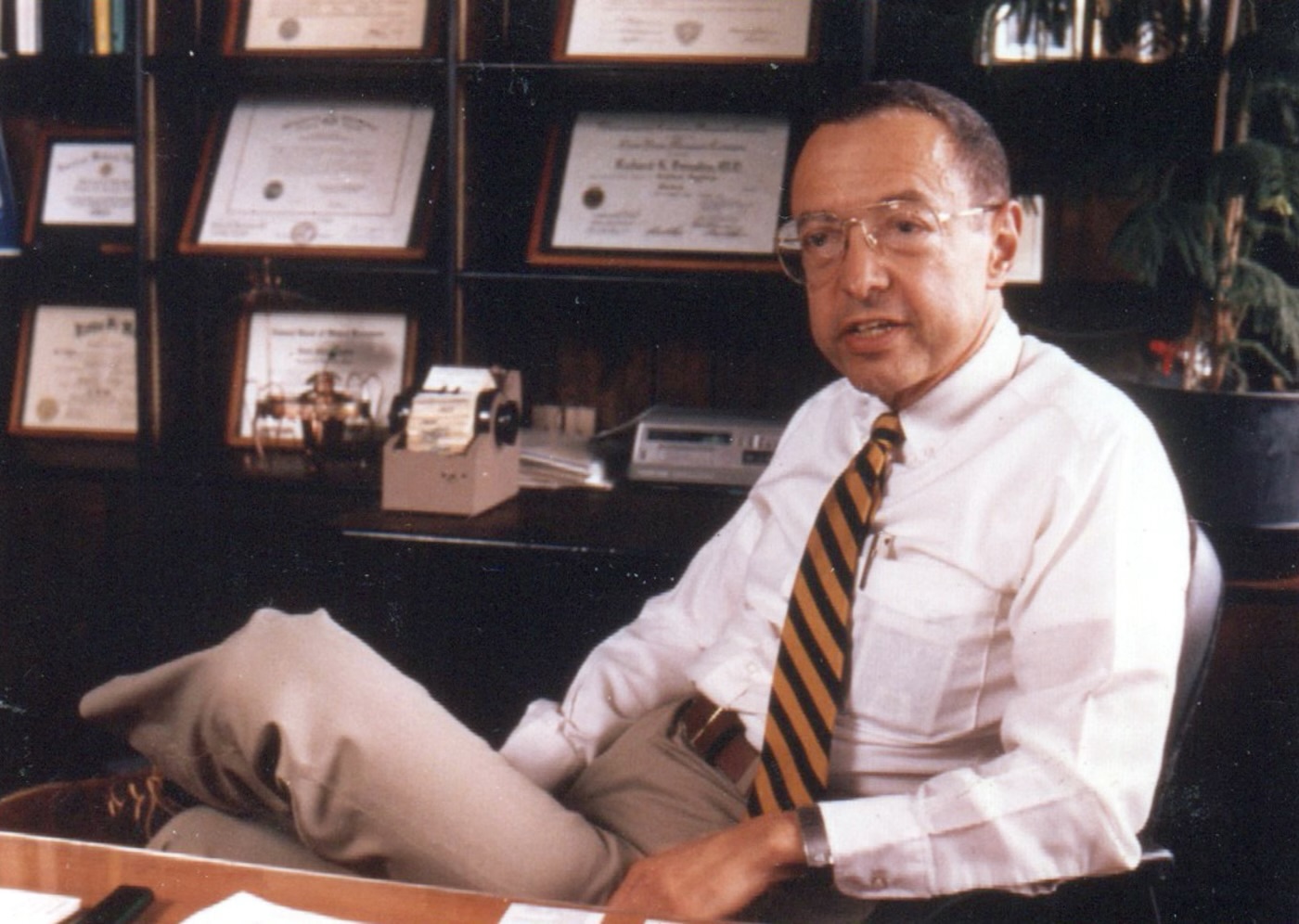

Ignored by the medical establishment, Bernstein went to medical school in his mid-40s to gain credibility

Richard Bernstein was flipping through a medical trade journal in 1969 when he saw an advertisement for a device that could check blood-sugar levels in one minute with one drop of blood. It was marketed to hospitals, not consumers, but Bernstein wanted one for himself. He had been sick his entire life and was worried he was running out of time.

A heavy, sick child, Bernstein was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 1946, when he was 12. As was common at the time, his treatment plan included a diet high in carbohydrates, a daily shot of insulin and a monthly visit to his doctor’s office to check his blood sugar. But it didn’t make him feel better. Things only got worse. By his 30s, he suffered from a frozen shoulder, deformed feet, night blindness, and was starting to wonder if he would live long enough to see his children grow up.

He wasn’t a doctor—he was an engineer with a degree from Columbia University—but he decided to explore new treatment options himself. Central to the process would be tracking his own blood-sugar levels, unheard of at the time. Since he wasn’t a doctor, the manufacturer wouldn’t even sell him a device. So, he bought one under the name of his wife, Dr. Anne Bernstein, a psychiatrist.

![]()